For 90 years we have relied on antibiotics and disinfectants to kill harmful bacteria and viruses. But with the rise of ‘superbugs’, a more preventative approach is being called for.

Drug-resistant microbes, such as methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) and clostridium difficile (C. diff), cause an estimated 7,000 deaths in Australian hospitals a year. According to the Department of Health and Ageing, approximately 180,000 patients suffer healthcare associated infections (HAIs). While HAIs increase the risk of morbidity it also costs the system on average an extra 18 hospital days and $37,500 per patient.

The workplace is not immune to this risk. Heated, airtight, indoor environments can become germ incubators in winter. Absenteeism due to sick days cost the Australian economy $7 billion, according to a 2015 report by AIG, with the flu alone responsible for an estimated $90.4 million of that. 100 years after the Spanish Flu killed 15,000 Australians, many experts believe that the next flu pandemic is a timebomb waiting to happen. But what has this got to do with cleaning?

Why focus on surface hygiene?

While hand-hygiene remains the most important way to prevent the spread of infection, in healthcare we’re seeing a renewed focus on cleaning the environment (surfaces) that hands touch (called touch points). Adding to the drive to improve cleaning practices, is the fact that superbugs are becoming resistant to disinfectants as well as antibiotics.

Furthermore, bacteria are colonising crevices in the surface under their own protective coating called ‘biofilm’. This coating is so hard, that a quick wipe will not remove it and a spray of disinfectant cannot penetrate it.

Even without the protection of biofilm, some bacteria and viruses have been shown to live a scarily long time on hard surfaces. For example, common cold and flu viruses are viable (able to make you sick) for up to 24 hours. Norovirus and C. difficile, both of which cause gastro, can survive for weeks – the latter being found to last five months!

Any organic matter found on a surface, be it food, bodily fluids or a dry spec of dust, is a ‘reservoir’ for microbes to grow in. When you touch a soiled surface, you also pick up a smorgasbord of microbes – some potentially harmful – and spread them to the next surface, hand or food you touch.

How clean are your building surfaces?

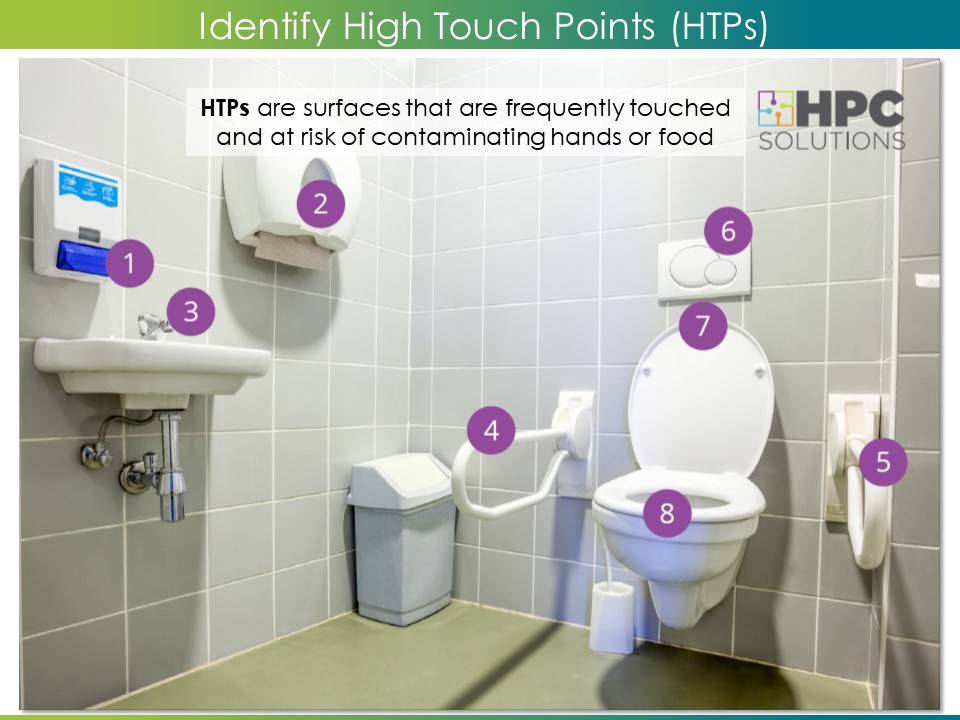

Of course it’s not viable, or practical, to have every surface wiped after they’ve been touched in a commercial facility. But it’s critically important to ensure surfaces which are frequently touched and at risk of contaminating hands or food (High Touch Points), are adequately cleaned at least once a day, to prevent the build-up of soil and prevent microbes from multiplying to unhealthy levels.

Effective cleaning and good surface hygiene should be a fundamental part of protecting worker’s wellbeing and preventing workplace absenteeism. But for too long, after-hours cleaning services have been literally out of sight, out of mind. They are viewed as a maintenance cost, rather than an important strategy for keeping people healthy. Surface hygiene has relied on the smell of disinfectant, ignoring the cleaning process.

For example, if the cleaning cloths used to clean the surface aren’t clean, they simply spread soil and germs from one surface to another. Damp, soiled, cloths and mops, draped over equipment or left inside buckets, are breeding grounds for germs – which are then spread around the facility the following night.

Yet our experience has shown that equipment for cloth laundering, air drying, and sufficient quantities of cloths is rarely supplied. Some newer buildings don’t even contain cleaner’s store rooms with cleaner’s sinks to enable this to occur.

Does it matter? Are building surfaces really that unhealthy as a result? Well, that depends on how surface hygiene is being measured.

Validated cleaning

Visual performance auditing is the common way of assessing cleaning performance – on hospitals as well as commercial facilities. While simply looking at a surface can tell you how shiny a floor is, or how many spots on mirror there are, it is a very inaccurate way of measuring surface hygiene for two key reasons:

- Germs are invisible.

- Visual perception of ‘clean’ is highly subjective.

A “validated” cleaning performance requires scientifically testing surfaces after cleaning to ensure all contamination has been removed. While there are several methods for testing surface hygiene, such as swabbing and ATP1, their uptake has been slow due to the expense and sensitivity, plus there are no recognised Standards against which to score the results.

Another approach is to require the use of cleaning and disinfecting products that have been validated as effective. “Evidence-based” cleaning is a key requirement for infection control in healthcare. So let’s explore the available options.

Unfortunately, unlike the USA which has a Standard Test Method for Evaluating the Effectiveness of Cleaning Agents (ASTM G122), there is no equivalent Australian Standard for testing cleaning products. TGO 54 is a standard2 for testing the germ-killing capacity of Hospital-grade disinfectants, but this method tests the solution not the surface.

Simply stipulating the use of disinfectants does not guarantee surface hygiene. That is because disinfectants can’t disinfect a surface if the soil has not been cleaned away first, or if the cloth is dirty, the technique is poor – or if the surface is missed altogether! A further limitation with TGO 54 is that it does not allow for testing the efficacy of physical cleaning methods such as microfibre technology.

I’m not arguing that validating the effectiveness of the cleaning method and its performance is not possible or important. It is. But it is the process of cleaning that determines the outcome. Simply measuring the outcome, regardless of the method, is like shutting the gate after the horse has bolted. I believe that a more holistic, process-driven and preventative approach to surface hygiene is needed.

Taking a preventative approach to surface hygiene

HPC Solutions™ has developed a HACCP3 style, risk-based criteria framework for High Performance Cleaning (HPC), in-line with the Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare.

The HPC Criteria for Hygienic Cleaning allows us to identify where risks of contamination, poor performance and the spread of infection lie, throughout the cleaning process. We can then establish critical control points to meet four broad objectives:

- To supply effective cleaning methods (i.e. testing cleaning agents, tools and techniques)

- To prevent contamination of surfaces (i.e. while carrying out duties)

- To maintain clean tools (i.e. laundering between shifts)

- To measure cleaning performance (i.e. UV Fluoro lighting4 or ATP testing on high touch points)

The HPC Solutions Compliance package guides cleaning services through a four step program:

- Map their entire cleaning process, end-to-end, in a Cleaning Plan.

- Conduct a Method Assessment against HPC criteria to identify areas of risk and control points.

- Validate the new cleaning methods and document them in visual training manuals.

- Audit compliance to the validated cleaning plan and test cleaning performance on high touch points.

We can achieve the best results by facilitating partnerships between the occupants (Facility Manager) and Cleaning Contractors. We want you to be able to go home confident that your cleaning services are proactively preventing sickness and workplace absenteeism through better surface hygiene.

Notes:

- This article was first written for Facilities Perspective Magazine, in October 2018. As I rewrite it today for the HPC Solutions website, a new flu pandemic, Coronavirus, is hitting China hard and spreading internationally. There are no vaccines yet. Preventative, validated Surface Hygiene is more important than ever.

- This article focuses on the Hygienic Cleaning Criteria as part of the High Performance Cleaning (HPC) criteria framework.

Definitions:

1. ATP: Adenosine Triphosphate is a protein molecule found in all living matter. ATP testing devices use fluorescence to measure the level of ATP as an indicator of how clean a surface is.

2. TGO 54: A disinfectant testing standard managed by the Therapeutic Goods Administration.

3. HACCP: Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points.

4. Fluorescent UV marking: Invisible fluorescent gel is applied to high touch points prior to cleaning, then checked after cleaning using an ultraviolet light to determine.