A simpler model for specifying and measuring cleaning standards

With the issue of unrealistic productivity rates and insufficient hours allowed for cleaning in Victorian public schools in the media, it’s a very fitting time to take a fresh look at the way we set cleaning performance standards and how they relate to productivity rates.

Everybody loses in this story: the students, parents, teachers, Principals, cleaners, cleaning companies and the Government. And yet nobody seems to know what to do about it.

Since I began writing cleaning specifications ten years ago, I have constantly looked for simpler and more accurate ways to write and price cleaning requirements, without compromising on accountability. When I came up with a completely new model we call the ‘Cleaning Activity Levels’ (CAL), I really thought it was too simple to be functional.

But it’s not – it works. We are now using the CALs model to:

- Schedule cleaning efforts more efficiently

- More accurately cost the labour requirements

- Simplify the way cleaning duties are communicated

- Provide a consistent and objective auditing framework

I believe that this model has too much potential to keep to ourselves so I’m sharing it far and wide at conferences and in articles. It is my hope that it will eventually be adopted as the basis for National cleaning standards and will change the way we set productivity rates so that everybody wins.

Re-think cleaning standards

Over the last ten years, I must have reviewed hundreds of cleaning guidelines, international standards and service specifications. In this time, cleaning specifications have shifted from a simple list of duties such as: ‘clean toilets daily’ or ‘dust desks weekly’, to wordy, complex legal documents – some are over 100 pages long and require a law degree to understand!

As English is a second language for many cleaners, I wanted to develop a less complicated way to communicate cleaning duties. However, complexity isn’t the only issue. The whole approach to setting and measuring performance outcomes is fraught with problems.

One night, at 2am to be precise, I awoke with a question: “why do cleaning standards always focus on the type of soil to be removed?” I jumped out of bed and scribbled down a diagram that became the Cleaning Activity Levels – affectionately known as ‘CAL’.

Before I explain how it works, and why I believe it could radically improve the way we specify, measure and communicate cleaning standards in Australia, let me explain what I believe is wrong with the current model.

Current cleaning standards

In the drive for greater accountability, cleaning standards have become long lists of every possible type of soil that a surface must be free of (i.e. the desk shall be free of dust, debris, spillages and smears), while performance is rated by visually assessing how much of that dirt is left behind:

1 = lots of dirt (fail) and

5 = no dirt (excellent).

While there are no National environmental cleaning standards, the Cleaning Standards for Victorian Health Facilities, 2011, is being followed by several other States and New Zealand. We expect hospital cleaning standards to be detailed due to the high risks of infection, and this document doesn’t disappoint: it contains 6 pages of performance standards for cleaning each type of building element found in hospitals and covers five separate aspects that must be cross-referenced:

- Building areas / elements / surface materials

- Risk categories and priority areas

- Cleaning outcomes defined via soil types to remove

- Frequencies and timeframes

- Auditing and scoring methodologies

And yet, even in healthcare, cleaning standards are defined by the types of soil that must be removed from each surface, and measured via visual assessment.

This requires auditors to look at a surface and determine how much of each soil type is left on it – a process that is neither consistent, accurate nor objective. And it certainly cannot be called “evidence-based”.

If we think about it, this approach actually defines an unclean surface – not a clean surface. And it can’t factor in how dirty the surface might have been before the cleaner started, or how frequently the surface was touched, or the time, effort, skill, equipment and process required to clean it.

You may be asking – but why can’t cleaning professionals just do what is needed? Isn’t that their job? Well, money, of course.

Most occupant organisations out-source their cleaning services in Australia, even in health and aged-care facilities, and we proudly boast some of the highest productivity rates in the world. (Meaning we clean really fast!) So let’s explore the way cleaning specifications for contracted services are modelled, and some of the related issues.

Prescriptive specifications

Prescriptive specifications detail every cleaning duty and when to do it. Some, like this horrific example, contain so many daily tasks they are impossible to deliver, setting the cleaner up for failure and creating an adversarial relationship. Issues with this approach include:

- It leads to arguments over minor omissions and how long dead flies should remain on stairwell window ledges, or if coffee spills should be cleaned the night they occur, rather than wait till Friday because that’s when the spec says to spot clean carpets.

- It undermines the cleaning operator’s skill and autonomy to assess the daily priorities as they see them and encourages short-cutting.

- And it has very little relationship with the m2 productivity rates that were used to cost the tender.

The reality is, that even if the contract specifies “vacuum traffic areas daily and full areas weekly”, cleaning staff only vacuum the dirt they see because that is how their work is judged. Consultants like me love to adjust frequencies in the scope of works to give our clients efficiencies, but this saving is actually impossible to measure using the current pricing model.

Performance-based specifications

Performance-based cleaning standards, on the other hand, are non-prescriptive and leave processes and even task frequencies to the expertise of the cleaning company. Performance measures often rely on subjective visual auditing carried out by the cleaning supervisor, and by the number of occupant complaints.

However for performance specifications to work, it is essential that the standard of ‘clean’ is clearly defined and communicated, or differing expectations about what is an acceptable level of clean between the cleaning company, the client and the staff and visitors, will lead to conflict.

The need for a new approach

Which brings me back to my 2am question: Why do cleaning standards focus on the type of soil to be removed? That’s a standard based on failure, not success. Shouldn’t a just-cleaned desk look the same regardless of whether it once held a coffee spill, dust or a paper clip? Won’t the damp cloth that wiped the coffee rings away, also remove dust and paper clips?

However, that same damp cloth may not remove the dose of E-coli or swine-flu that’s lurking on the desk. It may even leave some germs behind, after picking them up from one of the other 50 desks it just wiped, or from the edge of the waste cart it was hanging over…

But here’s the rub – no one will know what made the office worker sick if cleaning performance is judged visually, because you can’t see germs. And in an era of superbugs and flu pandemics, that is a problem.

First I wrote down three core principles:

- A surface cannot be accurately defined or measured as ‘partially clean’. It is either clean or unclean.

- The cleaning outcome is determined by the cleaning process: the method, the degree of effort and the frequency.

- Cleaning standards must be defined by how cleanliness is to be measured.

Then I mapped out a model that could be applied to any list of surface elements in any building, that I called the ‘Cleaning Activity Levels’ or the CALs.

The ‘Cleaning Activity Levels’ model

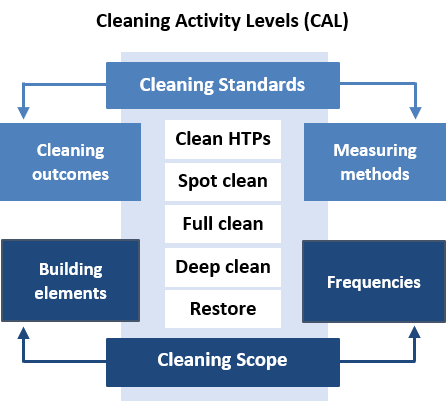

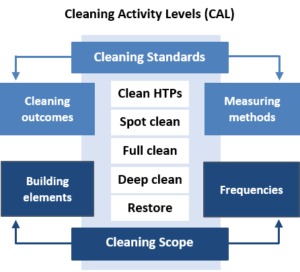

The ‘Cleaning Activity Levels’ model has applied definitions to common cleaning terms, by describing five different degrees of effort, or levels of activity, that cleaners are to carry out on a surface. The above diagram works like this:

- The upper half of the CAL diagram illustrates how cleaning standards are set by describing the required cleaning process and outcome, and how the performance outcome of each activity level should be most accurately and viably,

- The lower half of the diagram shows how these standards can be documented in cleaning specifications and schedules.

Using the CALs model to set Cleaning Standards

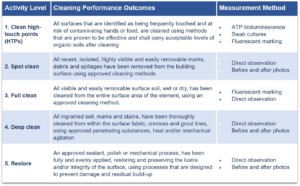

The 5 Cleaning Activity Levels define the cleaning process as well as the outcome as listed in the table below:

Applying the CALs model to Cleaning Specifications

CAL can dramatically simplify the way Cleaning Specifications are written, because the same outcome per level of activity can be applied to all surfaces, soft or hard. For example, if the cleaner is required to spot clean a carpet to remove ‘isolated, recent, highly visible and easily removable marks, debris and spillages’, then it is their responsibility to identify the recent spots and to decide how best to remove them. This could be vacuuming up a piece of lint and/or damp blotting a coffee spill.

The CAL model can also be used to structure the organisations requirements per specific building area, surface type (‘elements’), materials, risk priorities, hygiene, safety and sustainability initiatives.

As shown in the lower half of the diagram, CAL is applied to the Scope of Works (or work schedules) by setting the required cleaning levels, and how frequently they are carried out, for each area/building element.

We communicate this via a simple matrix that can be varied according to the level of risk, usage, and of course, your budget.

The benefits

One of the key benefits of CAL is that it respects and improves the cleaner’s skill, which could help to drive a renewed interest in training qualifications. Because it was built to integrate with the CAMS building hierarchy, it is also be easy to apply efficiencies and to integrate with maintenance information systems (MIS). This in turn will enable future predictive maintenance and flexible scheduling models, in a way that improves the quality and efficiency of the service.

The CAL model gives cleaning contractors the knowledge to improve efficiencies, and to leverage this expertise to increase customer satisfaction and profitability by:

- simplifying the way we communicate cleaning duties,

- providing a consistent and objective auditing framework,

- focusing the cleaner’s efforts and workflows more efficiently, and

- giving cleaners more autonomy and better cleaning skills.

Because high standards of cleaning cannot be achieved without adequate hours, a clear definition of what is expected and an objective means of measuring the outcome.

Let’s start a conversation

I am sharing the CALs model because I want to see the development of consistent cleaning standards that measures the process of cleaning as well as the outcome in Australia (and internationally). Let’s take cleaning into the 21st century, put some science behind and raise the bar for all.